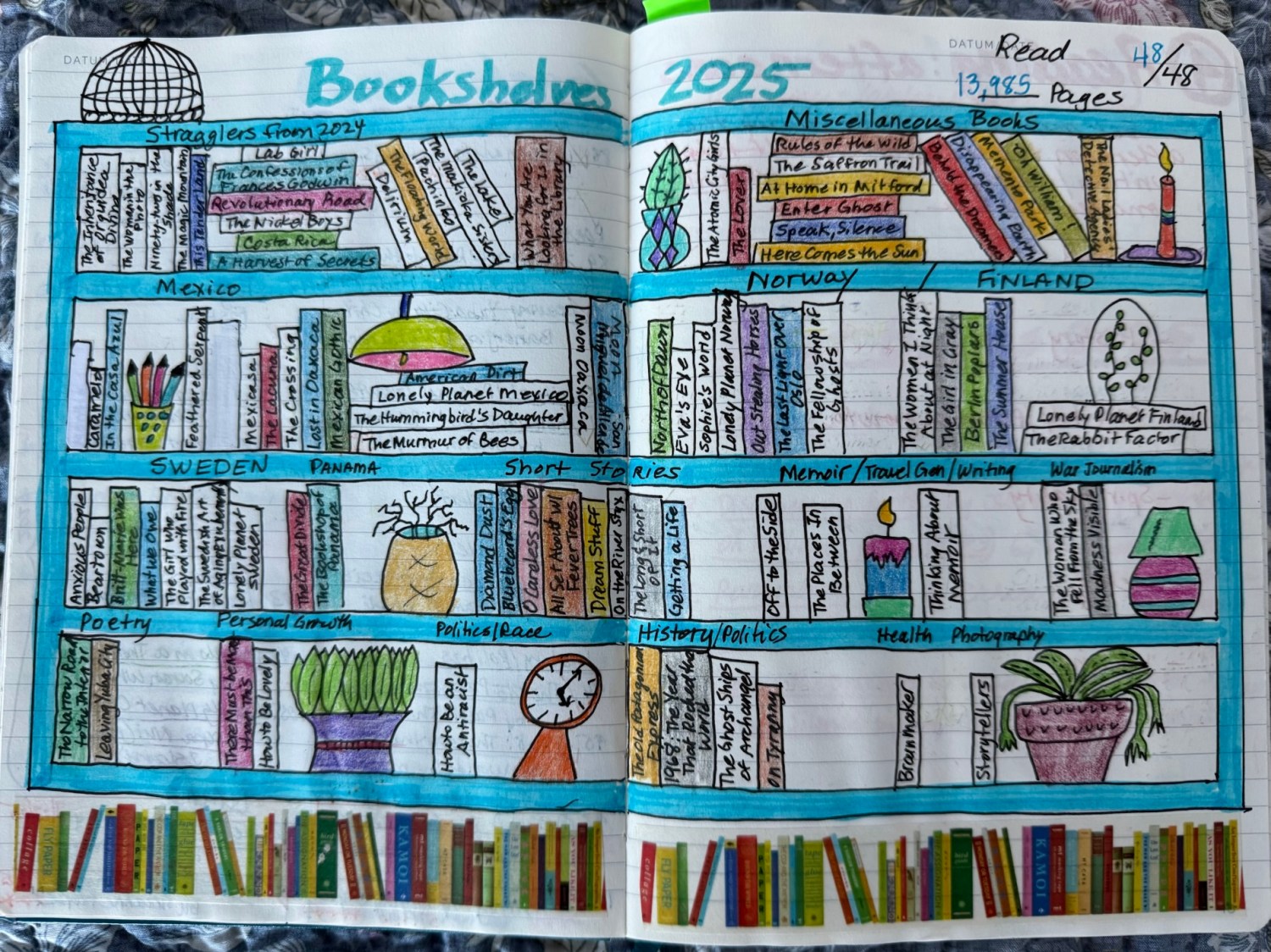

I choose many of my books for the year either based on my planned travels for the year, or from my huge book collection. On this year’s list, I picked books that took place in Mexico, Costa Rica and Panama, among other places. I read 48 books in total, with 6 taking place in Mexico, 1 in Costa Rica, 2 in Panama; I also read books set in the Norden countries of Finland (3), Sweden (2) and Norway (3) in preparation for our 2026 travels. In all, I read some 13,985 pages. The average length of books I read was 291 pages. I also read 7 short story collections.

I tried to incorporate more nonfiction and historical fiction into my reading this year to expand my knowledge and open my horizons. I learned a lot about the year 1968 (1968: The Year That Rocked the World by Mark Kurlansky); the beginning of the Nazi invasion of Norway in WWII (The Last Light Over Oslo by Alix Rickloff); the Finnish Winter War of 1939-1940 (The Girl in Grey by Annette Lyon); Indian boarding schools and The Great Depression (This Tender Land by William Kent Kruger); Mexican and U.S. history including Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and Leon Trotsky, as well as the McCarthy years (The Lacuna by Barbara Kingsolver & In the Casa Azul: A Novel of Revolution and Betrayal by Meaghan Delahunt); the building of the Panama Canal (The Great Divide by Cristina Henríquez); South and Central America in 1979 (The Old Patagonian Express: By Train Through the Americas by Paul Theroux); Italy during WWII (A Harvest of Secrets by Roland Merullo); the war in the Balkans (Madness Visible: A Memoir of War by Janine Di Giovanni and Speak, Silence by Kim Echlin), and varied accounts of the immigrant experience (American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins, Behold the Dreamers by Imbolo Mbue, North of Dawn by Nuruddin Farah, & What We Owe by Golnaz Hashemzadeh Bonde).

My 2025 bookshelves from my bullet journal

Here, you can see my 2025 Year in Books. Below are my 10 favorites + two bonus books. They’re not in any particular order except the order in which I read them.

1) American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins *****

Jeanine Cummins has written a riveting tale of a woman and son from Mexico who are forced to migrate to “el norte.” Lydia is a middle class woman who runs a bookstore in Acapulco and is married to journalist Sebastian. Acapulco has been experiencing gruesome violence due to drug cartels. The city is being terrorized and people are afraid to go out in public. Her husband writes an exposé about the head of a new drug cartel, Los Jardineros, that is threatening the established cartels in Acapulco. It turns out this jefe is nicknamed “La Lechuza,” or The Owl, because of the glasses he wears. When Lydia puts two and two together, she realizes La Lechuza is a man, Javier, who has been visiting her in her bookshop, and with whom she shares a love of books. He is poetic, this man, and it seems he might be in love with her to some degree. When Lydia reveals her friendship with Javier to her husband, he asks her to carefully read the article before it goes to press; she assures Sebastian that Javier will not have a problem with it; that no violence will come to Sebastian or their family.

However, things don’t go to plan, and one awful day soon after the article’s publication, during Lydia’s niece Yénifer’s quinceañera, or 15th birthday, while 16 members of Lydia’s family, including Sebastian, are celebrating in the backyard, they are all gunned down – murdered in cold blood – by Los Jardineros. Lydia and Luca, her 8-year-old son, happen to be in the bathroom during the murders and manage to evade the killers.

Thus starts the long journey of Lydia and Luca to escape without a trace to “el norte.” Lydia and Luca have seen the violence that befell their family, and Lydia knows Javier will not rest until she and Luca are dead.

The story tells of all the hardships and dangers the two encounter as they slowly and doggedly make their way north, out of Javier’s reach. The book is a page-turner, and it dives deep into the migrant experience. It gives backstory and a face to one of the thousands of migrants that make their way across the border of Mexico’s northern neighbor each year. An excellent rendering of people trying to survive and thrive under terrifying circumstances and threats to their lives.

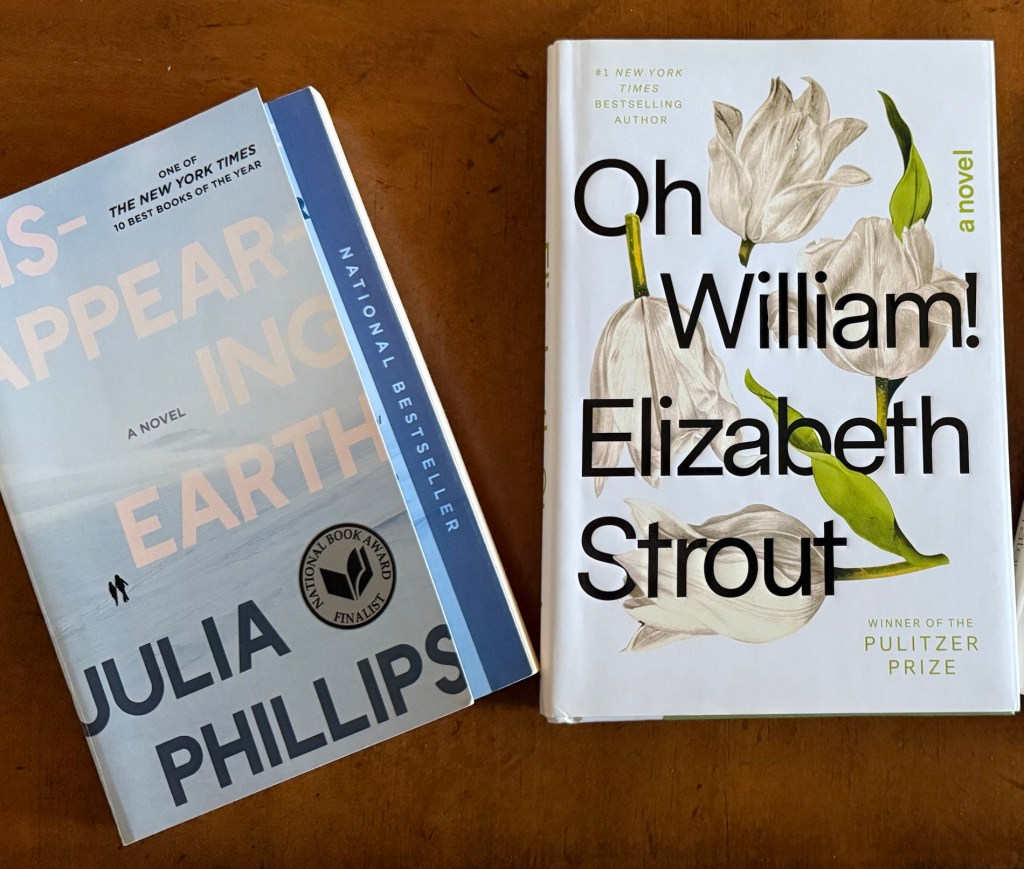

Disappearing Earth and Oh William!

2) Disappearing Earth by Julia Phillips *****

On an August day, while their mother Marina is working as a journalist, two young girls, Sophia (8) & Alyona (11), go missing from a beach in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky on the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia. The first chapter reveals their abduction, but nothing more is revealed of their fate. Instead, the author introduces the reader to various characters and their lives, people all aware of the abduction of the two girls. Their lives have been impacted or curtailed due to this highly publicized disappearance. The awareness of the girls’ unknown fate puts everyone on edge; people are already struggling with personal turmoils in their lives and relationships before this darkness descends.

Reading about these characters shows the harsh reality of life in this far-flung region of Russia. It turns out there are indigenous people from the North; one of them had a teenage daughter disappear years before, but the police never took the case seriously. They tried to convince the family that the daughter simply ran away. But the mother always felt the daughter was murdered and the police didn’t care enough to investigate.

In a book such as this with so many characters, the author provides a much-appreciated chart at the front of the book listing the different families and their relationships and jobs. There is also a map of Kamchatka which I also appreciated, although it would have been nice to have a bit more detail to it.

Overall, the book was a fascinating look into the lives of people living in the hinterlands of Russia and their struggles and deepest dreams, hopes and fears.

3) Oh William! (Amgash #3) by Elizabeth Strout *****

This was my 5th Elizabeth Strout book, and I have loved them all. This one cements my appreciation of this author for all eternity. She tells a story of a woman, Lucy Barton, who suffered horribly through an impoverished and abusive childhood, yet still finds joy in her life. In this book, she tells the story of her relationship, both past and present, with her ex-husband and now friend William. She married him, she felt safe with him, yet she also felt he was absent somehow. She felt he had “authority,” which gave her peace of mind after her terrifying and uncertain childhood. But as William is revealed, we see all of his faults, and Lucy’s as well, and we understand deeply how flawed people are; we humans are all flawed.

William finds out he has a half-sister, Lois Bubar, who he never knew about. His mother, Caroline, had left her husband, a potato farmer in Maine, and daughter, Lois, to run off with a German POW after WWII. William is the son of Caroline and that father who fought on the side of the Nazis. When William finds out that he has a half-sister, he asks Lucy to accompany him to Maine to check into his sister. Together, they find out some surprises about William’s mother and his half-sister and about the impoverished Maine towns that his mother came from. Lucy meets Lois Bubar, but Lois declines to meet William, her half-brother, who sat in the car waiting.

The countryside of Maine passes outside their car window: “We passed by a restaurant whose paint was peeled, it had obviously long been closed, but in square letters out front was a sign that said: AM I THE ONLY ONE RUNNING OUT OF PEOPLE I LIKE?” They see an old couch sitting in the middle of nowhere, a man glaring furiously at them as they drive by, boarded up towns, and the impossibly tiny dilapidated house where Caroline grew up. All of this is a shock to both of them.

Lucy tells of someone she met as a freshman in college, someone ten years older than she was. He didn’t really seem her style after she got in his car that had cup holders in the armrests. “But I liked him, I probably loved him. I fell in love with everyone I met.” I could relate to this from my own college years.

Lucy has just lost her dear second husband, David. There are two daughters from William and Lucy’s marriage, Becka and Chrissy who are now adults. Lucy looks at William and sees the things she saw in him when they were first married, and then she sees in him the things that caused her to leave him. Ever changeable, William defies understanding. Oh William! And Oh Lucy!

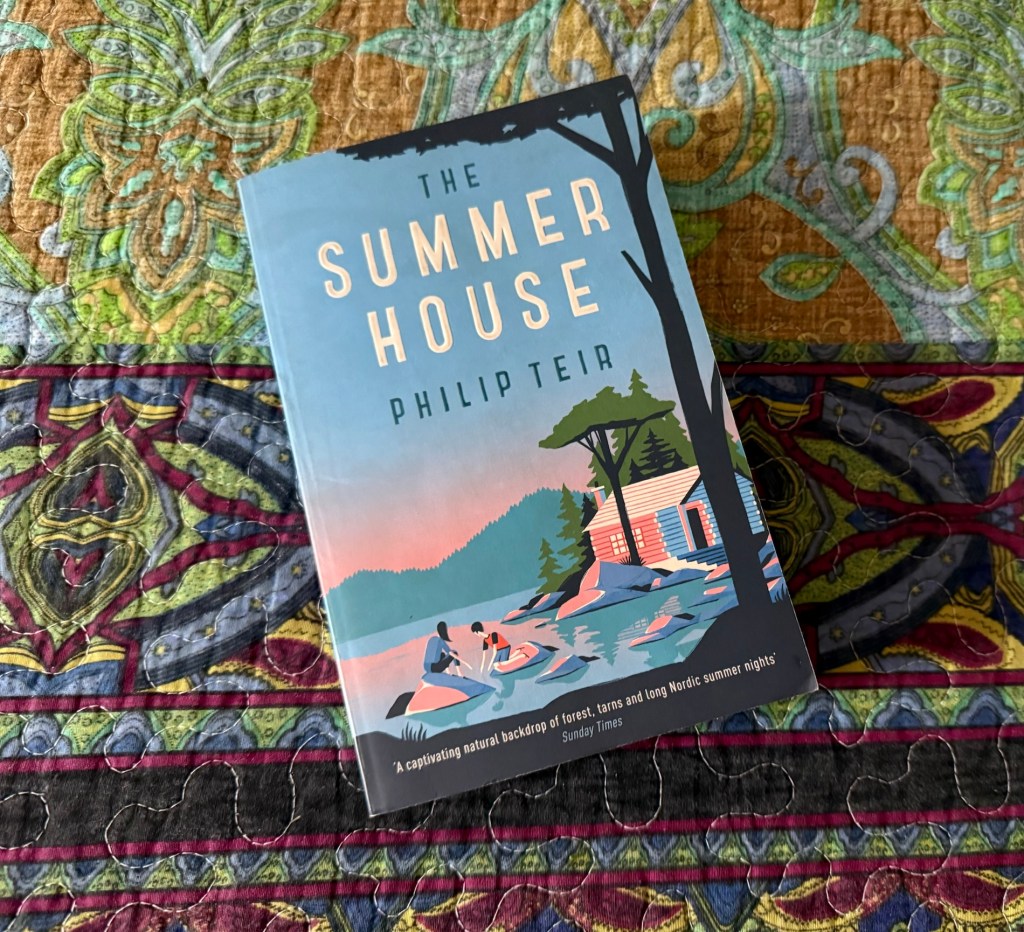

The Summer House by Philip Teir

4) The Summer House by Philip Teir ******

I really loved this summer escape to the Finnish seaside through this family of four: Julia and Erik and their two children, Alice and Anton. Like every family, they come with baggage. Erik has been sacked from his mediocre job at a department store but hasn’t told his wife. Julia is a novelist who will spend her summer writing her next book. She had written one before about her childhood at this same summer home, which the family hasn’t visited in years, and her childhood friend Marika. She had somehow felt oppressed by Marika as a child; Julia hadn’t been in touch with her in years. But the family discovers that Marika is visiting her family home with her husband, Chris, who has some strong beliefs about the environment. Chris and Marika had been environmental activists but now “formed a loose-knit group in Scotland whose purpose – and the whole thing sounded a bit vague to Julia – was to prepare for living in the world after climate change. And they had decided that Mjölkviken was the perfect place from which to welcome the apocalypse.”

This is NOT a futuristic or dystopian book. It is a book relevant to the current times, though it was published in 2018. The cast of characters also include some random people who are part of the “movement,” Kati, a grieving woman therapist, Chris’s 13-year-old son Leo, and Erik’s brother Anders. All of them are struggling with personal failures or dilemmas or life decisions, both past and present. I really love this kind of slow-moving book that explores the issues of the day and personal struggles of the characters.

5) Behold the Dreamers by Imbolo Mbue ******

This book takes place during the 2008 financial crisis, when the main character, a Cameroonian immigrant, Jende Jonga, is working as a chauffeur for Clark Edwards, a senior executive for Lehman Brothers. Jende gets along well with Clark, and in addition he drives Clark’s wife, Cindy, and their children Vincent and Mighty, various places. As a quiet and observant chauffeur, Jende overhears phone conversations that reveal the troubles at Lehman Brothers and troubles in the family: Vincent wants to go to India for “enlightenment” and wants to shun all the materialism and consumerism of America. Of course his parents had higher hopes for him and are upset and disappointed by this decision. I personally can relate to this; although we are not even close to being in the upper 1%, our son also chose to throw off the consumerism in the U.S. and escape to poverty-stricken Nicaragua to live a “simple” life.

There are problems in both families. Clark’s wife Cindy is needy and suspicious of her husband’s long working hours. She abuses drugs and alcohol. At one point she asks Jende to keep a book detailing all the places he drives Clark. It’s a no-win situation as Jende knows he often drops Clark at the Chelsea Hotel, and so, in loyalty to Clark, he changes all the Chelsea drop-offs to “the gym.” Cindy has promised Jende will never lose his job as long as he reports the truth to her. This situation creates a major tension and turning point in the book.

Jende’s wife, Neni, loves New York and the promise of America. She is going to school in hopes of becoming a pharmacist, while raising her six-year-old son Liomi and being pregnant. When problems start to arise over Jende’s legal status, and the family begins to suffer from the recession and money worries, Jende and Neni are at odds over whether to return to Cameroon or continue to struggle in the U.S.

The best thing about this story is that it puts this Cameroonian family in the center of the immigration debate that has been ongoing in the U.S. We are a nation of immigrants but under the current administration, the U.S. is seeking to purge our country of black and brown skins, creating a white supremacist society. Even Jende finally recognizes that people like him will always be struggling just to keep their heads above water. The focus of the book on two families of different social classes, the wealthy 1% and the immigrants seeking a better life, shows the stark divide in this country between the haves and have-nots, and how horrible it is for people who are forced to live in poverty and, basically, as slaves to the wealthy. For this timely story, which could easily be set today as in 2008, this is great read to understand the different forces at work in American society.

6) Speak, Silence by Kim Echlin *****

This wonderful but disturbing novel tells a fictional story based on the Foča trial of 2000 at The Hague. Gota Dobson is a journalist who goes to Sarajevo to write about a film festival and to look for an old lover, Kosmos, who is also the father of her child Biddy. Kosmos is from Sarajevo and he has always been in love with Edina, who was one of the rape victims held hostage during the war. Edina would become a witness in the trial, along with many other women who were repeatedly raped, beaten, tortured and held captive during the war. Edina was in love with Ivan; she, Kosmos and Ivan had been childhood friends. Gota becomes captivated by the trial and decides to stay in Sarajevo and then go to The Hague to write about the horrendous story. She befriends Edina and together they navigate the suffering that the war inflicted, particularly on the women, as well as the legalities of the trial. She listens to the witnesses who come forward reluctantly, unwilling to relive the abuse they suffered, in the public eye.

This is a slim but powerful novel about the atrocities human beings commit against one another, and the slivers of love, as well as the will to live, found among the ruins.

7) Out Stealing Horses by Per Petterson *****

This dreamlike book tells a complex & ever-unfolding story of a boy on the cusp of becoming a man. We start by looking back: Trond Sander is 67 years old and has moved to a small house in the far east of Norway, almost on the border with Sweden. Here Trond hopes to simplify life, to escape from Oslo and commune with nature. He hasn’t shunned the world, in fact he listens to the radio all the time, but when he listens to the news “it no longer has the same place in my life. It does not affect my view of the world as once it did.” He has longed all his life to be alone in a place like this, and the only company he has is his dog Lyra.

But a person cannot be so easily shed of his past. He meets his lone neighbor, Lars Haug, and soon after, a summer from his past comes to him. It was 1948, and Trond was 15 and spending the summer with his father; the two of them had gone to this place on the edge of Norway, surrounded by wilderness. Trond remembers a July morning at this place when his dear friend Jon came to his door and said they were “going out stealing horses.” After they had their fun with the horses, in which Trond was hurt and cut by barbed wire, Jon led him to climb up a tree, where Jon acted senselessly and cruelly. It turned out that Jon had been responsible for a tragedy the previous day that involved his younger twin brothers, the same Lars he met at age 67, and his twin brother Odd.

This complex story tells of Trond and his enigmatic father, who had been involved in the war effort against the Germans. His father had his own ideas about what it meant to be a man, and he had his own particular way of doing things. Trond loved and admired his father immensely, but over time his admiration was challenged by a course of complicated events.

The writing in this book is spare yet poetic, and Petterson captures so well the elusive nature of life, relationships and emotions so that the reader is carried along on the journey, open to whatever transpires. There is sadness, joy, and a tangle of emotions to explore. It was an immensely enjoyable read.

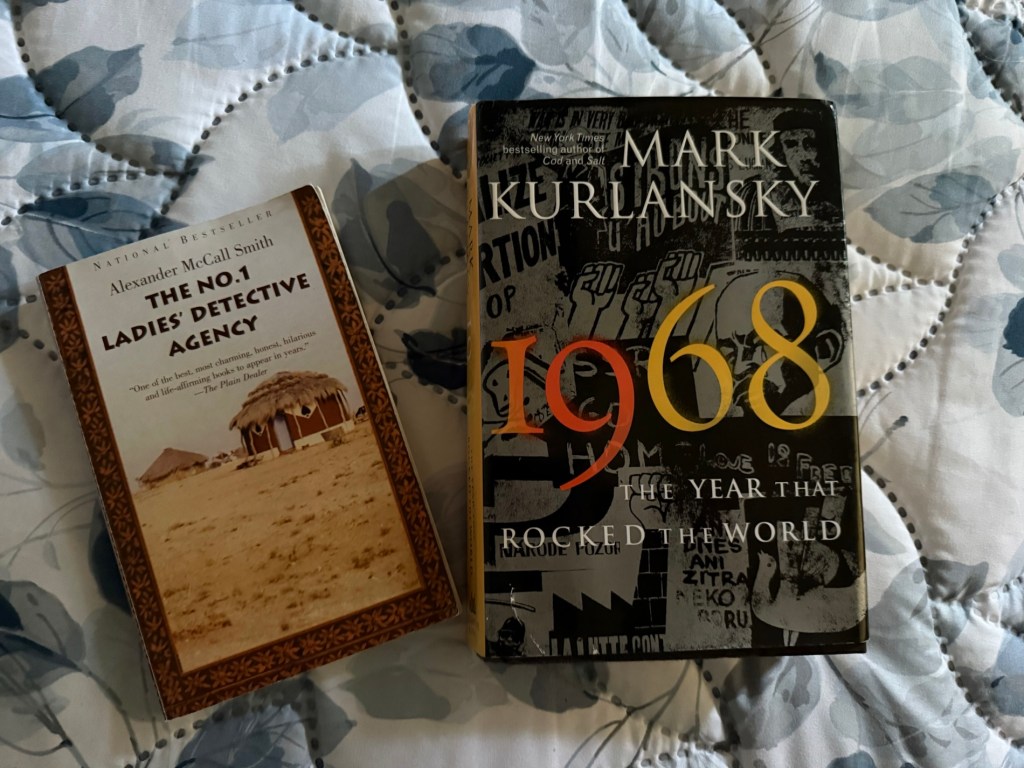

The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency & 1968: The Year that Rocked the World

8) The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency by Alexander McCall Smith *****

I was pleasantly surprised and charmed by 35-year-old Precious Ramotswe, a self-assured, wise and round (in the “traditional” way) woman who, after her father dies leaving her many head of cattle, sells the cows and opens a detective agency.

She worries about making enough money in fees to support herself but her reputation builds quickly and the local citizens increasingly seek her out to help them solve problems. Missing husbands, insurance fraudsters, fake fathers, vanishing sons, and witch doctors feature as her clientele’s problems to be solved.

The story gives interesting background about Precious’ father, her childhood, her first husband, and her friends, as well as the land and culture of Botswana. The story is well written and straightforward with a twist of humor.

It was a pleasurable read all around.

9) 1968: The Year that Rocked the World by Mark Kurlansky *****

I was only 12-13 years old in 1968 but I remember well the images on TV of the Vietnam War, the student riots, the invasion of Czechoslovakia, and the Black Panthers. Of course I remember the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy. Even though I didn’t understand everything that was happening at the time, the images were so seared in my mind that I felt I needed to read Mark Kurlansky’s excellent historical account of that pivotal year. I found it an excellent book. Since I was too young to be fully immersed in events of that time, I can’t account for whether Kurlansky’s book includes all the important points of view or all the watershed moments. But I learned a great deal from reading this book, especially about the student uprisings that were all over the world, not just in the U.S., and all the political movements coming head-to-head during the year.

The thing I remember most from that year was my father, a staunch Republican, screaming and yelling at the TV about hippies, black people, and the anti-war movement. I believe he was even happy that King and Kennedy were assassinated. My upbringing by that hateful and racist man shaped me to become the polar opposite of him: I’m an anti-war Democrat, a person with an open mind who cares about humanity and equality and women’s rights and the plight of the poor. I see clearly the dangers of unfettered and unregulated capitalism. The greedy and powerful will always want to control everything they can, and there is no limit to their greed, their conniving, and their selfishness. And despite all they’ve accumulated, they can’t be bothered to give back to the society which gave them the tools to succeed. The world still hasn’t found its way; even now in 2025, 57 years later, I see we still haven’t progressed much since that year. I thought we had, but I see too many similarities between today and that year of upheaval.

Despite all the horrible things that happened in 1968, I found this quote especially enlightening: “The thrilling thing about the year 1968 was that it was a time when significant segments of the population all over the globe refused to be silent about the many things that were wrong with the world. They could not be silenced. There were too many of them, and if they were given no other opportunity, they would stand in the street and shout about them. And this gave the world a sense of hope that it has rarely had, a sense that where there is wrong, there are always people who will expose it and try to change it.” (p. 380).

This is the hope embodied in the year of 1968, and in this book.

Rules of the Wild: A Novel of Africa by Francesca Marciano

10) Rules of the Wild: A Novel of Africa by Francesca Marciano *****

This book is hands down my favorite book read in 2025. How have I missed reading this author before now? This story made me immediately want to take the next plane to Kenya; it only helps that I recently met a wonderful Kenyan lady who is gentle, wise and inspiring; a woman I have great respect for. She had already piqued my interest about her country; this book led to me being utterly besotted.

This novel though is about white people living in Kenya. The narrator is Esmé, a beautiful Italian woman who arrives in Nairobi with a boyfriend after losing her beloved father Ferdinando; she decides to stay behind in Nairobi without the boyfriend when he leaves. She soon falls in love with Adam, a second-generation Kenyan who leads safaris in the wild. She is amazed by the kinds of people she meets in the circle of expats living there: journalists, documentary filmmakers, artists, relief workers, wildlife researchers. She seems mostly in awe of everything. She finds the landscape both alluring and inhospitable, and she doesn’t know how she will fit in, or if she ever will.

Despite being in a comfortable relationship with Adam, when she meets journalist Hunter Reed, she feels an immediate attraction, despite, or maybe because of, his outrage over the horrors, poverty and violence found in Africa, especially in Somalia and in Rwanda in the early 1990s. He sees things clearly and without the rose-colored glasses through which the other expats see Africa. Their attraction is fierce and to Esmé, this attraction feels dangerous. She’s in terror that she’ll be obliterated by Hunter and his power over her.

The writing in this novel is superb; I devoured every word. I loved being immersed in this world, and I still want – desperately – to stay in it. A wonderful, absorbing and utterly addictive story.

******

And here are two books that I think are very worthwhile reads: a book for the times and a book that lays bare the worst of humanity:

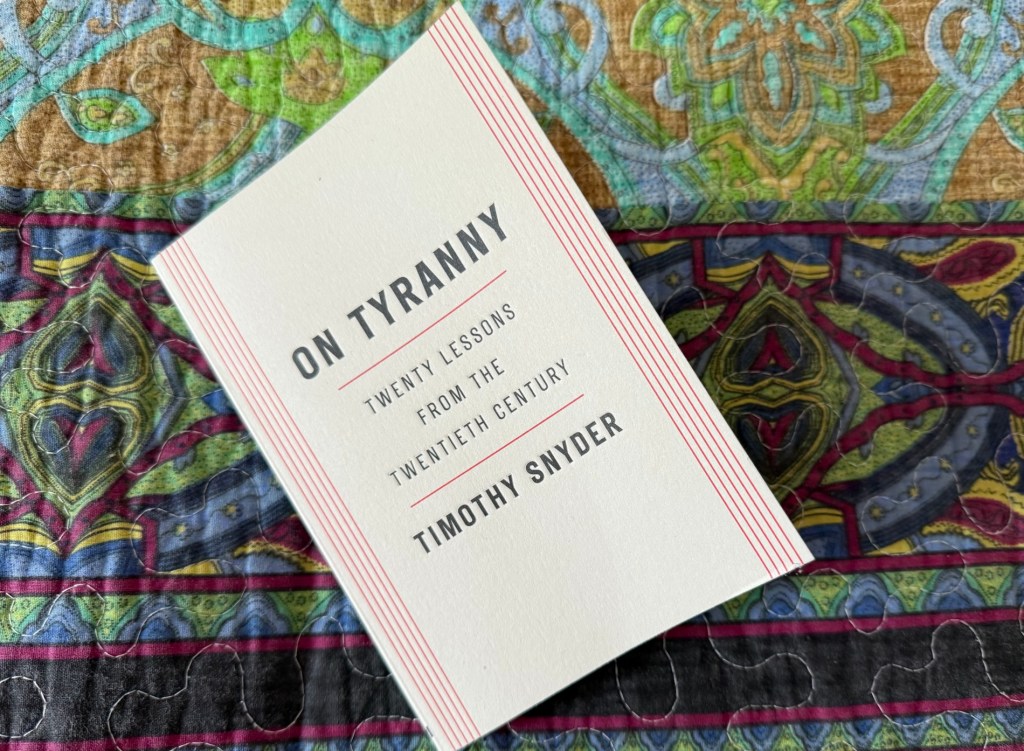

On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century by Timothy Snyder ****

On Tyranny – a book for the times

The similarities between our current regime in the U.S. (& other “national populist” – aka fascist – governments throughout the world) and 1930s Germany are made clear in this small book about how democracies become autocracies. Timothy Snyder outlines the twenty lessons from the 20th century about how the death of democracies comes about by a thousand paper cuts, through: degradation of the free press and institutions; proliferation of misinformation and outright lies; book banning and the dismantling of education (the dumber people are, the easier they are to control); the chipping away of civil rights of minorities and women; the ongoing threats to anyone who speaks truth to power and and the strongly worded (tweeted) DEMANDS for obeisance; the shedding of professional ethics; the hiring of thugs (masked “ICE” agents who don’t show any identification while basically “disappearing” people to prisons in another countries without due process) to do the government’s bidding; the rejection of norms; and the list goes on…. Every single one of these lessons are ones that we can see happening under our current regime. It’s no wonder it is said that Timothy Snyder left the country for Canada.

The only thing I would say could improve the book is for certain chapters to be more cohesive and on point, especially the Epilogue.

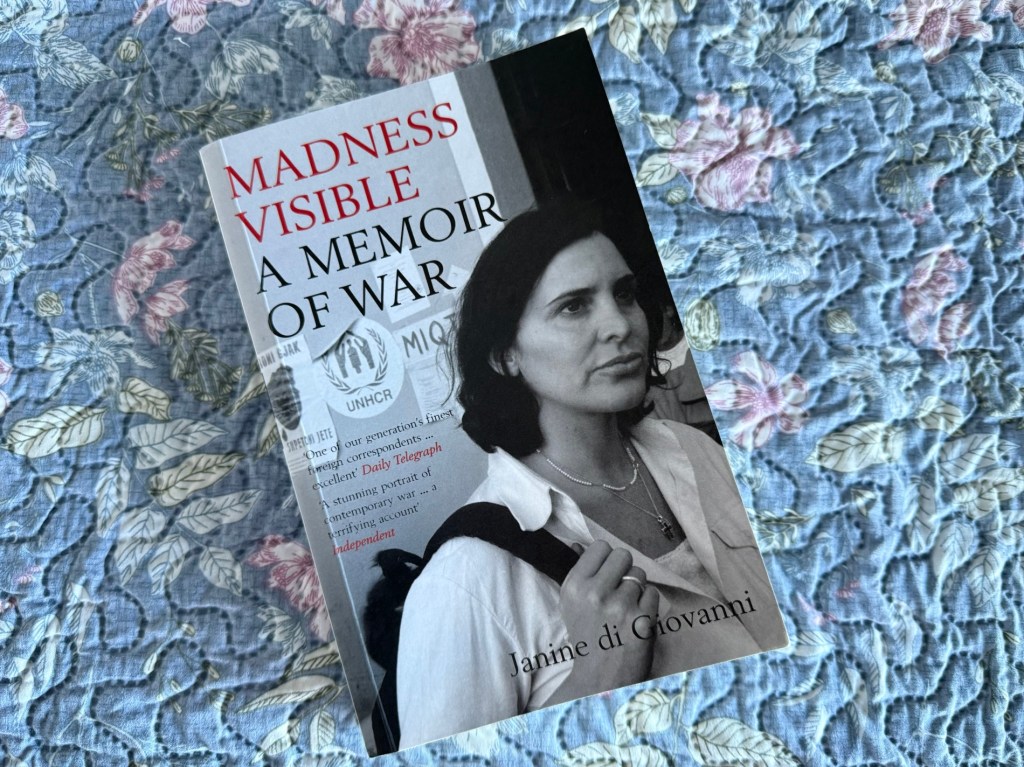

Madness Visible: A Memoir of War by Janine di Giovanni *****

Madness Visible: A Memoir of War by Janine di Giovanni

I bought this book in 2021 at a bookstore in Dubrovnik, Croatia called Algebra, which has a good English section. I remember asking the bookseller what book she would recommend so I could learn more about the Balkans and without hesitation, she handed me Madness Visible: A Memoir of War. I didn’t read it right away, but I should have. I should have known more about this war in the 1990s; I must have had my head buried in the sand.

Thanks to talented and brave journalist Janine Di Giovanni, I know more than I ever wanted to know about the horrific wars that took place over a decade in the former Yugoslavia. The book jumps back and forth in time, and shows the true cost of war: in deaths, in wounds, in destruction of homes and entire towns, in psychological damage. Men and boys were pulled out of their homes, forced to dig their own mass graves, and then shot and tossed into the graves. Many were tortured in concentration camps and then killed in terrible ways. Women were held prisoner and repeatedly raped. Many had babies from these rapes and then disowned them in shame. The damage was extensive and still continues today, even though the wars are over. For now.

The author tells the heartbreaking story of people that turned on each other over minor grievances, and then inflicted terrible things on them. Leaders, followed by their gullible masses, promised “pure homelands;” they dehumanized the “other,” and then together they destroyed everything: people’s homes, their lives, their last vestiges of hope. In this book, it’s the Serbs who were the most heartless, the most ruthless. They were determined to cleanse Bosnia of Muslims, and they did it without hesitation, with utmost cruelty and animosity; they became animals.

The Western powers that had the ability to stop it all sat on their hands and did virtually nothing until it was too late. What a travesty.

I applaud this journalist for laying bare the truth about a horrific tragedy, a failure of epic proportions, a descent into madness. It showed me exactly what human beings are capable of doing to one another when manipulated by leaders who are filled with hatred and want revenge and retribution.

What a gut-wrenching, heartbreaking, and devastating book.

***********

Did you read any great books this year? What were some of your favorites?

Discover more from ~ wander.essence ~

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Such an interesting list of books, Cathy. If you liked American Dirt, you may also like the book I just read by Seth Michelson, Hope on the Border: Immigration, Incarceration, and the Power of Poetry. Seth is a bilingual professor of Romance Languages here in Virginia and has served as translator, advocate, and even poetry therapist to immigrants forced into the detention centers here in the US or remaining in limbo at the border in the Mexican refugee camps. All of his stories are based on real people entrusting him with their experiences. It’s mostly heartbreaking (only about 1% of asylum seekers – people who are doing it the “right” way – are granted asylum. The rest get deported back into the same dangerous conditions they tried to flee from). It is very humanizing and allows the reader to look beyond the statistics. Seth did an amazing job connecting these individual stories with current politics and the obscene profiteering from these anti-immigrant politics. His final chapter focuses on what each reader can do to get involved. I read the book in one sitting, one night after dinner, into early morning, because I could not put it down.

LikeLike

Wow, that book sounds fascinating, Annette. I have put it on my “to read” list. Thank you for sharing that. I don’t know if I’ll get to it in 2026, as I already have an ambitious reading list ahead, but for sure I’ll try to read it in 2027. This problem will be going on a long time, I fear. There are so many great books about the immigrant experience; I wish people would try to understand the struggles of people trying to flee dire circumstances. But overall, I think most Americans are too selfish to care. I honestly believe reading benefits society but of course the current administration loves the uneducated. They’re much easier to control and manipulate.

Happy New Year to you and your family!

LikeLike

I have actually begun a research project which I hope will lead to a book: the contributions of immigrant women to the US. I have a number of responses already and it is such a privilege to hear every woman’s life story. I can’t wait to write it all up and share with the world!

LikeLike

I have only read two of these books, the Elizabeth Strout (I love her too) and the Alexander McCall Smith which I read many years ago when it first came out. I read the first three in the series and then gave up because they were all much the same and my enjoyment wore off. I tend to “go on a run” with an author I like: this year I’ve read several by Rose Tremain, Emma Donoghue and Rachel Joyce.

LikeLike

Give me any book by Elizabeth Strout and I’m happy! As for the Alexander McCall Smith books, I loved the first one but I can’t imagine reading a whole series. I mostly liked getting a small feel for Botswana. I’m developing an increasing interest in Africa lately.

I’ll have to look up the authors you mention. I saw the movie Room by Emma Donoghue but haven’t read any of her books. I’ve heard of Rose Tremain and Rachel Joyce but haven’t read any of them either. I’ll have to look out for books by them for future years!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an interesting and varied list. You did well to read so many books along with everything else you did this year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was a struggle to read so many books this year since we traveled so much. I don’t get nearly as much reading done when I travel. I think last year I read around 57 books (maybe?) Anyway, I hope to be more intentional about reading in 2026; I hope to learn a lot about the world and humanity. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person