My daughter informed me this morning that she wanted to go on a run and just have a leisurely morning; she didn’t want to accompany me to Charles Pinckney National Historic Site, Sullivan’s Island, or Fort Moultrie. I felt like there was still some residual anger and tension in the air over our arguments about TV shows and dining out from the night before. I wasn’t about to let her disrupt my travel goals, so I went out determined to enjoy my time.

However, I didn’t enjoy the time, not at all. It was gloomy and threatening rain, which often affects my moods. Also, I had been having dreams of escape lately, especially with all the stuff going on with our youngest son. I had dreamed of finding a job in Richmond and getting an apartment there where I could at least hang out periodically with Sarah. This morning, it was clear to me that moving to Richmond wouldn’t solve my problems, as my daughter didn’t seem to enjoy my company either. I felt anxious, more sure than ever that I was not made for motherhood, in fact, that I was a huge failure at it. I wished a huge sum of money would drop down from the sky, so I could move back to Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, or to a Greek island. I knew in my head that it wouldn’t solve my problems, but my heart was telling me otherwise.

So. I was in a dark mood as I drove under gloomy skies to the Charles Pinckney National Historic Site on Sullivan’s Island.

Charles Pinckney National Historic Site commemorates Charles Pinckney’s life of public service and contributions to the United States Constitution, and preserves a remnant of his 715-acre coastal plantation, Snee Farm.

Snee Farm

Charles Pinckney was a long-time advocate of a strong central government with clear separation of powers. He advocated for protecting property interests and helped to shape the U.S. Constitution.

Charles Pinckney National Historic Site

Charles Pinckney National Historic Site

Charles was born into a prominent Charleston family on October 26, 1757. His father, a wealthy planter and attorney, was commanding officer of the local militia, member of the General Assembly, and president of the state’s Provincial Congress.

Charles received his basic schooling from a South Carolina scholar who emphasized history, the classics, political science, and languages. Growing political unrest with Great Britain disrupted Charles’ plan to attend school in England. He ended up staying home and studying law with his father.

Charles Pinckney

In 1779, during the Revolutionary War, Pinckney represented Christ Church Parish in the State Assembly. As a lieutenant in his father’s militia regiment, he helped to retake Savannah from the British. The next year, after the British captured Charleston, he and his father were imprisoned along with other American officers. The older Pinckney was freed after swearing allegiance to the British Crown, which saved the Pinckney estate. Charles wasn’t released until June 1781.

In 1784, Pinckney became a delegate to Congress. In May, 1787, he and others represented the state at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. On May 23, 1788, South Carolina ratified the new Constitution.

In April of 1788, Charles married Eleanor Laurens and they eventually had three children. Over the next ten years, he held a variety of political offices, including Governor of South Carolina and U.S. Senator.

During his grand tour of the southern states in 1791, President George Washington breakfasted at Charles Pinckney’s Snee Farm.

In 1795, Charles Pinckney joined with Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic Republicans, championing the interests of rural Americans over those of the coastal aristocracy.

In the 1800 Presidential campaign, Pinckney was Jefferson’s South Carolina campaign manager. Jefferson rewarded Pinckney with the ambassadorship to Spain. Pinckney helped facilitate the acquisition of Louisiana from France and tried unsuccessfully to to get Spain to cede Florida to the U.S.

From 1806-1808, he served his 4th and final term as governor of South Carolina and he retired from the U.S. Congress in 1821. He died in Charleston on October 29, 1824 at age 67. He spent 42 years devoted to serving the community, the state and the nation.

Today’s Constitution includes some 30 provisions from the “Pinckney Draft”: a two-part legislature; a single chief executive; an annual State of the Union address; the emoluments clause (restricting government officials from receiving gifts or titles of nobility from foreign states); and protection of individual citizens’ rights.

Today’s Snee Farm, which is one of Charles Pinckney’s properties, consists of only 28 acres of the original property of 715 acres. Charles inherited it from his father. The present house was built in 1828 on the site of Pinckney Plantation House. It included a typical tidewater cottage once common throughout southern coastal areas. The ponds and fields were used for growing indigo, rice and cotton.

I watched the film, walked through the museum, and then walked on the trail.

Coiled basketry is one of the oldest West African crafts in America. Made from native sweetgrass and pine needles sewn with strips of palmetto leaf, this cultural craft appeared in South Carolina in the late 1700s. Originally designed as a tool of rice production and processing, the baskets were an authentic cultural connection for slaves to their native Africa. The craft has since been handed down through generations of the Gullah Geechee. Today, sweetgrass baskets are sold along roadside stands and markets throughout the lowcountry and are considered art for display as much as they are tools for use.

sweetgrass baskets

sweetgrass baskets

Utensils in slave quarters consisted of a large iron pot and a few hollowed out dried gourds.

implements

inside the Charles Pinckney house

fireplace in the house

African American slave

porch on Pinckney House

Pinckney House

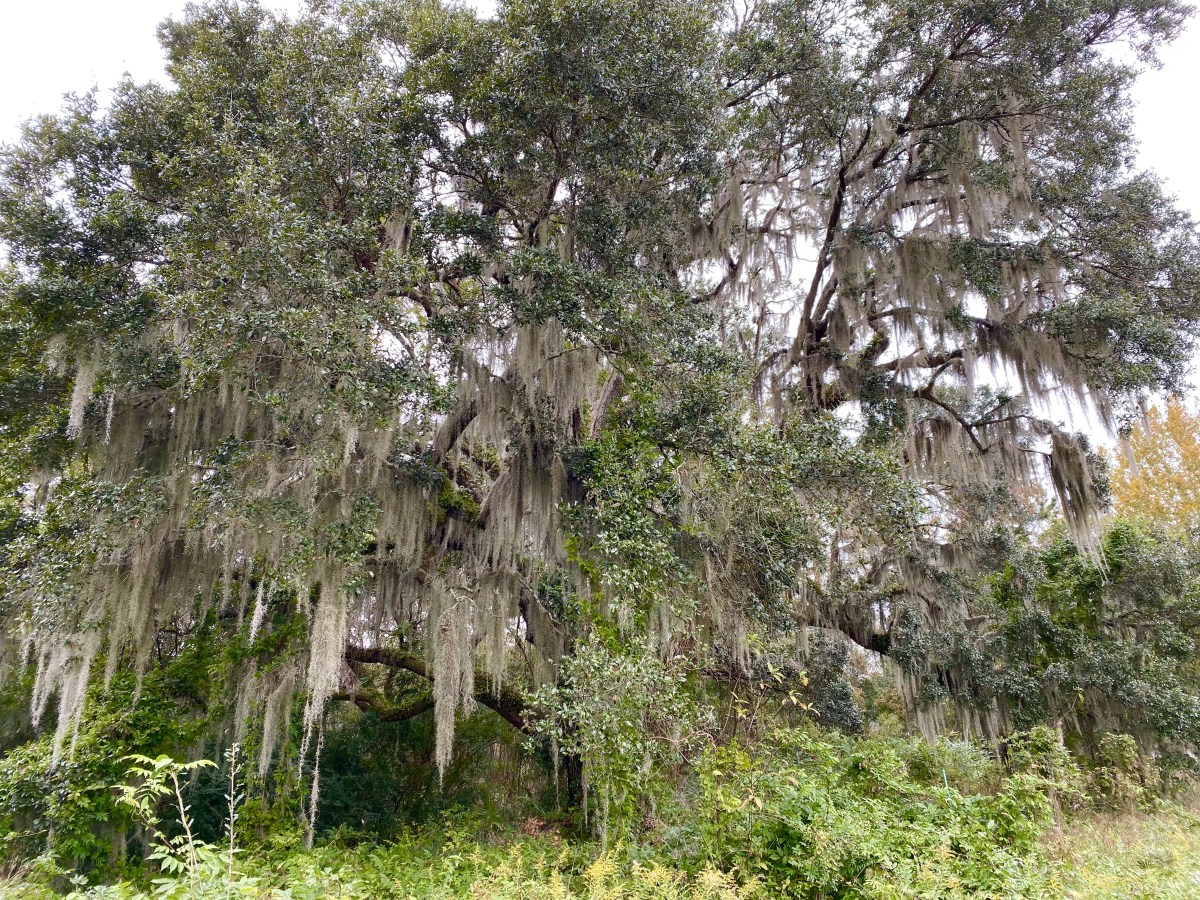

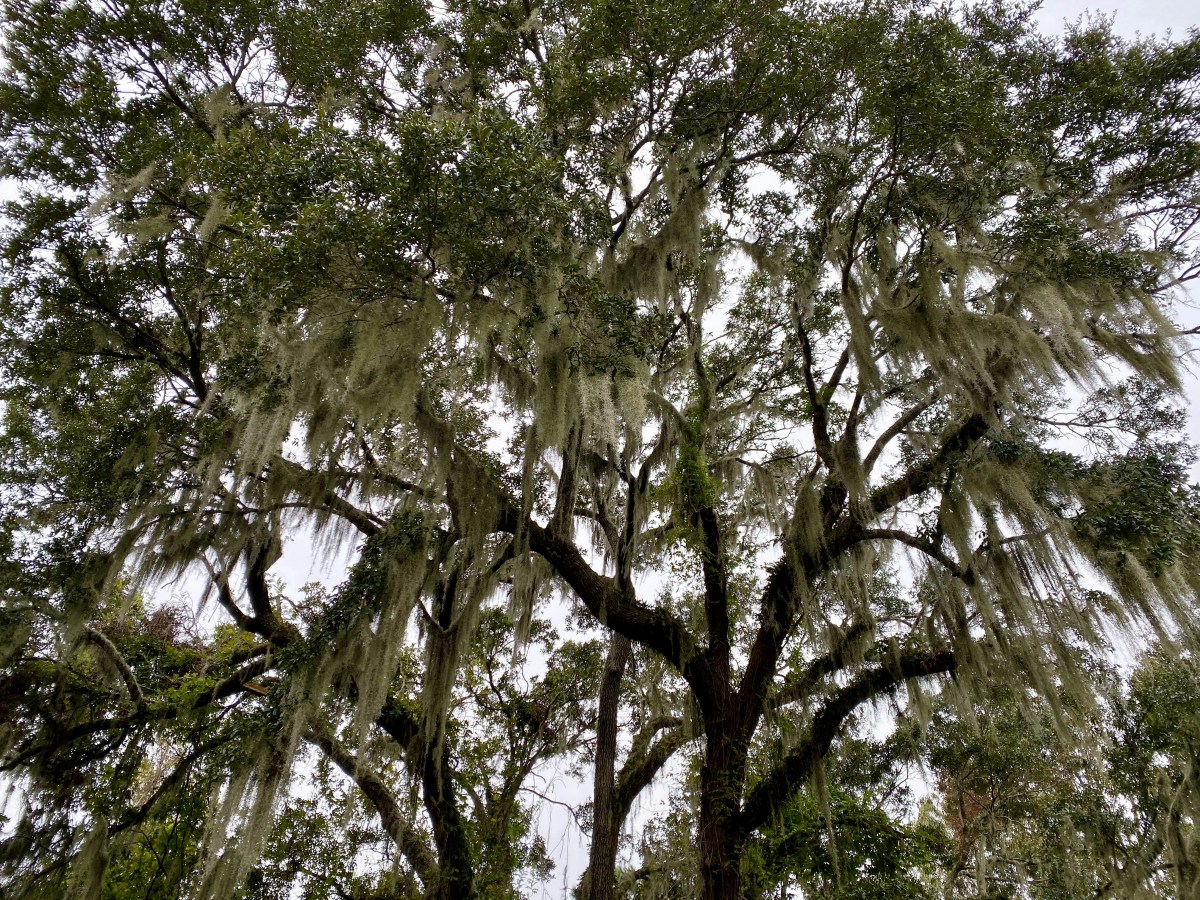

I strolled past native red cedars, remains of slave quarters, tidal wetlands, towering magnolias and live oaks, wax myrtle, yaupon holly, Spanish moss, palmettos, Sabal palmetto (Cabbage palm), Sabal minor (dwarf palmetto), and early imported plants that have naturalized, such as popcorn trees (Chinese tallow), wisteria and privet (ligustrum), native sea lavender and black needlerush.

Snee Farm

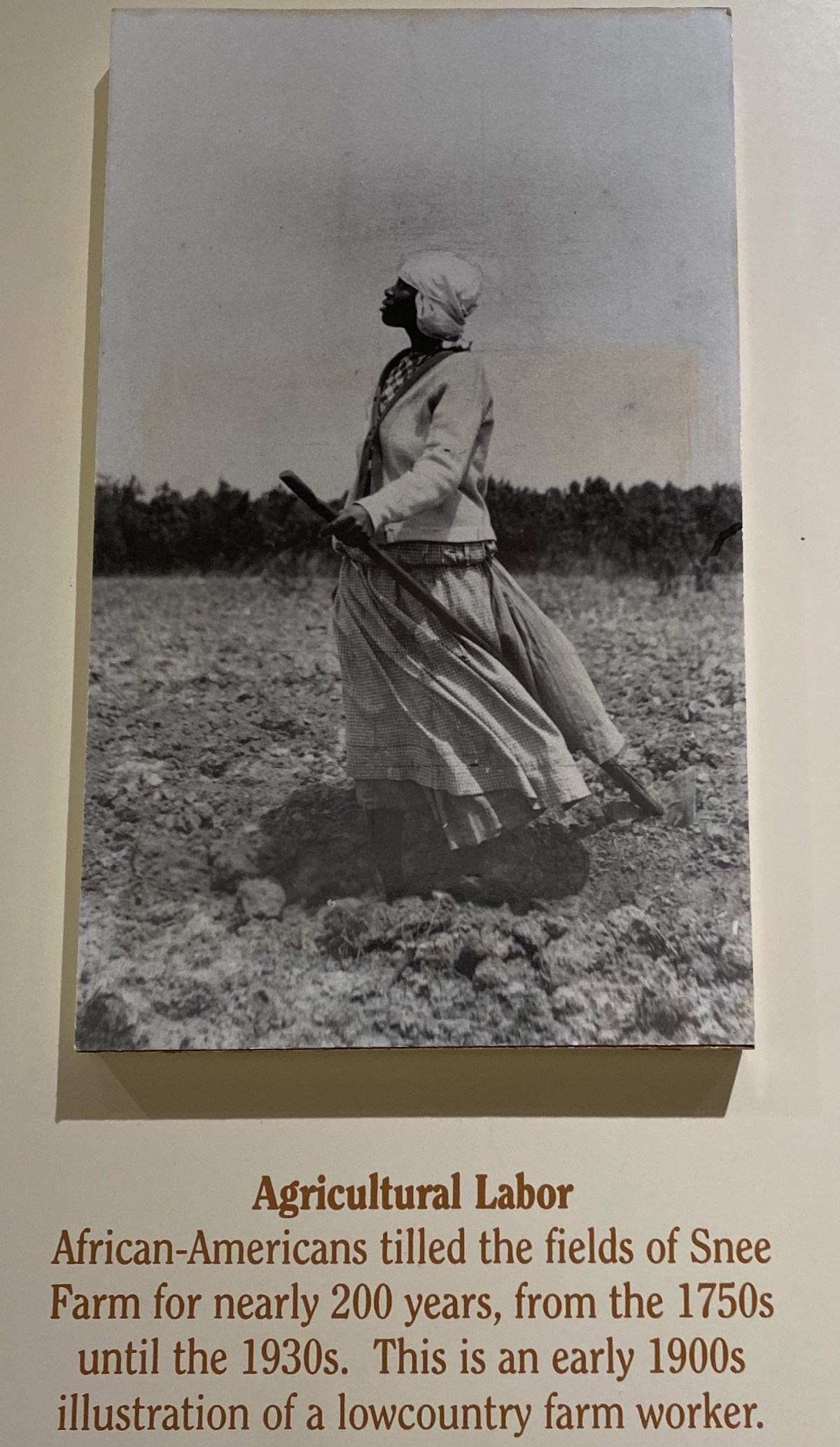

During Pinckney’s ownership, his property included 40-60 enslaved Americans, valued at £2,230 pounds in 1787. In 2000 U.S. dollars, this translates to $231,256.36. They tended the indigo and rice fields, and many were skilled wheelwrights, coopers, sawyers, carpenters, and gardeners.

“Carolina Gold” rice, along with indigo and cotton, fueled the economy of Charleston and the young nation as a whole. Farmers depended on slave labor to harvest crops. Enslaved Africans here evolved a common culture and language, known today as Gullah or Geechee.

Pinckney was a slaveholder and defender of the institution of slavery. He adamantly refused to allow even the mention of slavery into the U.S. Constitution, threatening to withdraw South Carolina support if the issue was addressed. Slavery formed the basis of the South’s economy. Many Southern representatives held the same view.

Archeological excavations uncovered evidence of three buildings used to house slaves.

Snee Farm

Snee Farm

Snee Farm

Snee Farm

Snee Farm

Snee Farm

Snee Farm

Snee Farm

I walked onto the boardwalk over a tiny branch of Wampacheone Creek, a tidal estuary, which joins the Wando River that empties into the Cooper boat landing on a larger creek. Rice and other table crops were floated by barge to markets in Charleston.

The marsh grass here is black needlerush, a coarse rigid grass with sharp tips.

boardwalk over tiny branch of Wampacheone Creek

branch of Wampacheone Creek

Snee Farm

Spanish moss

Snee Farm

I saw a model rice trunk, a device of West African origin, installed in embankments to control the flow of water to rice fields. During high tide, the gates on the river side would be raised to flood the field, and lowered to retain the water during tide shifts. When fields needed to be drained for weeding and harvesting, gates would then be raised during low tide and water would be released into the river.

Rice was the main cash crop of South Carolina until it was overtaken by cotton just before the Civil War.

Rice Trunk

drawing of rice trunk in the museum

Historically, indigo dye was extracted from three different plants of the same indigo genus. Eliza Lucas Pinckney, great-aunt of Charles Pinckney, and her enslaved workers were the first people in the colonies to successfully cultivate indigo in 1739. Pinckney shared her seeds with other planters, who learned how to efficiently grow large quantities of indigo. These improved growing methods made indigo dye a dominant export from Charleston in the early 1800s.

Indigo

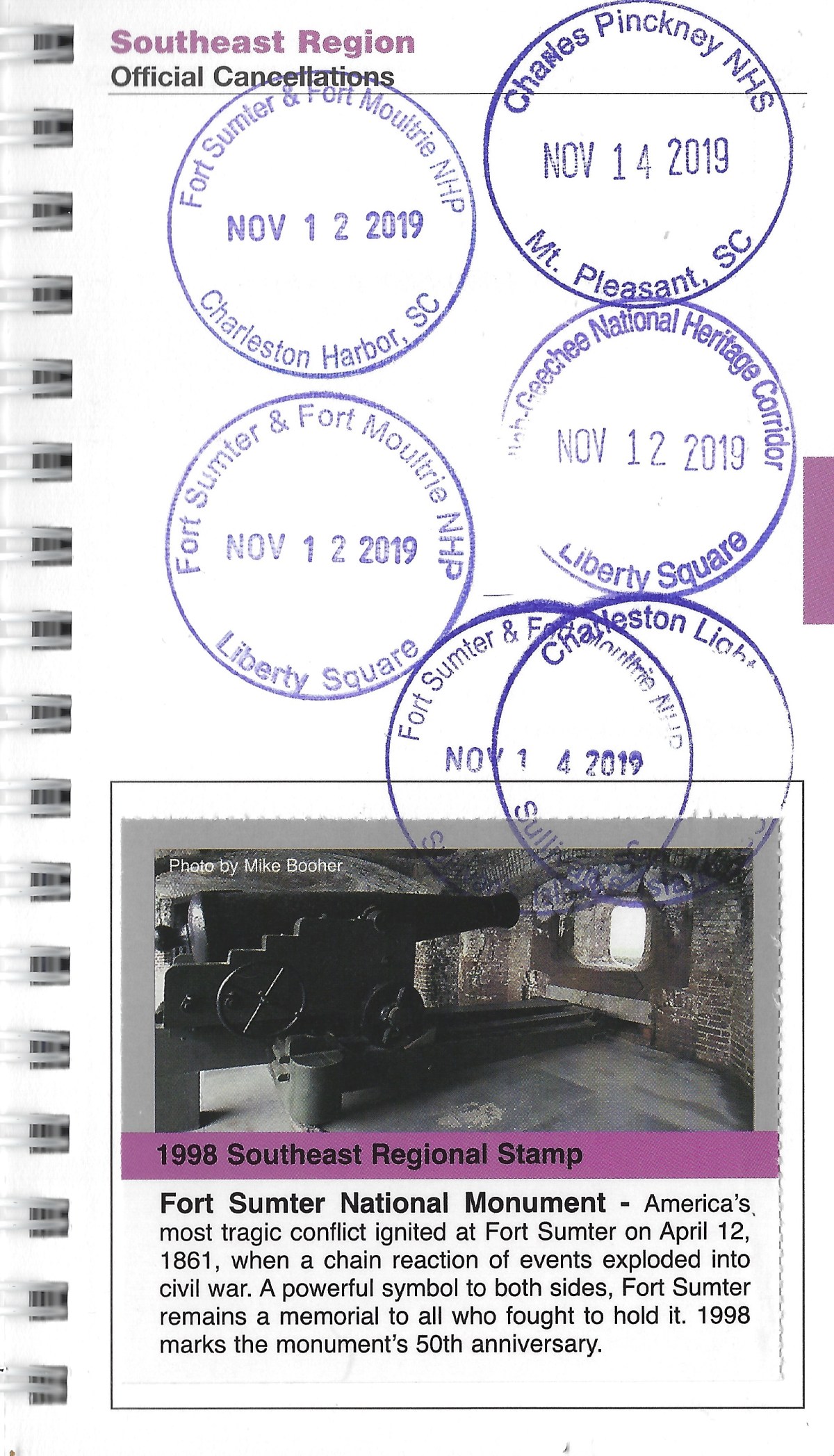

Below is my cancellation stamp for Fort Sumter, the Charles Pinckney National Historic Site, and Fort Moultrie.

cancellation stamp for Charles Pinckney National Historic Site

I left the Charles Pinckney site and Mount Pleasant and drove next through Isle of Palms and then to Sullivan’s Island.

Information about Charles Pinckney and the Historic Site is taken from signs at the site and from pamphlets published by the National Park Service.

*Thursday, November 14, 2019*

You must be logged in to post a comment.