I drove to Baltimore in late February to spend a weekend away while my husband went to his annual gathering with his high school friends. Maryland welcomed me with its state slogan: “We’re Open for Business.” I always wonder where states get their slogans. I stopped at a rest area, and within a half hour, I was in Baltimore.

Baltimore is only an hour and 20 minutes from where I live in Northern Virginia, so I don’t know why we don’t visit more often. This was my first time to this museum, and I was impressed by the exhibits and the building. This was my last outing before we were hit by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Baltimore Museum of Art is Maryland’s largest art museum. The collection was given by Baltimore philanthropists including the Cone Sisters, Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone.

Baltimore Museum of Art

The museum has two sculpture gardens, which I sadly missed.

“Mickalene Thomas: A Moment’s Pleasure” transformed the museum’s 2-story East Lobby into a living room for Baltimore from the 1970s and 1980s.

“Mickalene Thomas: A Moment’s Pleasure”

The exhibit had a strange film with little black cut-out paper dolls.

I found mosaics from Syria and present-day Turkey.

Spencer Finch | Moon Dust: NASA’s 1972 Apollo mission returned to earth carrying samples of dust from the moon’s surface. Spencer Finch replicates the chemical composition of that substance in this installation, in which 417 LED lightbulbs are configured on fixtures, mimicking the patterns of molecules in moon dust. Each bulb represents one element bonded in these molecules: oxygen, magnesium, silicon, aluminum, calcium, titanium, chromium, or iron. The heavier the element, the bigger the bulb. Suspended on cables at exact intervals, the fixtures form a three-dimensional scale model that is also an abstract sculpture.

Gazing up, one has the sense of being immersed in a star-filled sky.

Spencer Finch / Moon Dust

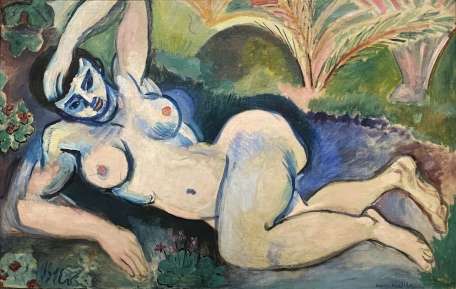

In the exhibit “A Taste for Modernity,” artworks that were once contemporary are now historic. Baltimore had accepted modernity in the arts by the late 1700s. During the 20th century, Baltimore’s taste for the modern continued with avid interest in European and American avant-garde painting.

I ran into an interesting alcove with some colorful ceramics and stained glass.

I walked through another exhibit: “Free Form: 20th-Century Studio Craft.” The term “free form” captures the invention, spontaneity, and organic abstraction that energized and united mid-century American art, craft, and design. Studio crafts artists of the time enhanced their art with found materials and new fabrication techniques. Working in embroidery, ceramics, and jewelry during the 1940s to 1970s, artists focused on the use of line, color, texture and form, reflecting a shift towards an avant-garde engagement with abstraction.

Another exhibit was on modern art.

Another exhibit was “By Their Creative Force: American Women Modernists.” This exhibition explored the range of American women’s creative force in a survey of modernist art and design across painting, sculpture, printmaking, and ceramics from about 1915 to 1955. These artists, from a variety of geographic and socioeconomic backgrounds, engaged with the major styles of their times, including Cubism, Precisionism, Bauhaus, Geometric Abstraction, Surrealism, and Abstract Expressionism.

Red Bowl, 1953 by Grace Hartigan

Georgia O’Keeffe completed more than 200 paintings of flowers during her lifetime. In Pink Tulip, the artist used feathered, blended brushwork to produce smooth surfaces and organic shapes alive with color. Combined with a close-cropped focus on her subject, her technique presents the tulip as a living, changing blossom. Critics often wrote that her flower paintings evoked the human body.

Pink Tulip, 1926 by Georgia O’Keeffe

Of course, every museum must have an exhibit on Impressionism.

The Cone sisters were ardent collectors. Claribel Cone (1864-1929) and Etta Cone (1870-1949) formed one of the world’s most important collections of European modern art during the first five decades of the 20th century. Raised in Baltimore, the sisters were part of a large, close-knit family whose shared success in the grocery and textile industries provided them with lifelong financial security. Claribel, the older sister, had a distinguished medical career at a time when women did not regularly attend medical school. Etta, the younger sister, did not have a career but was an accomplished musician and managed the household for her family. Neither sister married or had children, but the family fortune allowed them to collect art, travel, and pursue their own interests freely.

When drawn to compelling painting, drawing, or sculpture, they found it difficult to resist its pull. The same was true of small items of lesser consequence that filled their drawers to overflowing. They “bought passionately and by the dozens” and never threw anything away. The sisters stored their purchases in heavy chests and hundreds of beautiful boxes made of carved wood, leather, silver, lacquer, and brocade.

Collection of the Cone Sisters

Collection of the Cone Sisters

In 1917, Henri Matisse traveled to Nice, in the south of France, searching for new subjects to paint. The special quality of light and the congenial atmosphere of the Mediterranean coast inspired him, and over the next 25 years he spent at least part of each year painting there until he moved to nearby Vence during World War II. His works of this period are distinguished by an ever-increasing interest in light, color, pattern, and line. One of the greatest strengths of The Cone Collection is the impressive group of paintings from the artist’s early Nice period, generally considered to extend from 1917 to 1930. These works include landscapes, still lifes, interiors, and figure paintings that are admired for their colorful style.

Matisse painted women in interiors throughout the 1920s, but The Yellow Dress can be seen as a major change in his style. The painting combines the familiar elements of the Nice works — patterned floors and walls and shuttered windows — with an assertively monumental pose and central position for the figure.

The Yellow Dress, 1929-1931 by Henri Matisse

After studying in New York with William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri, Patrick Henry Bruce moved to Paris in 1903. He was quickly accepted into the Parisian art world and met leading avant-garde artists, which led to a major shift in his work. This modern flower study is an example of a series of still lifes that he produced from 1907 to 1912, which reflect his interest in Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse. Bruce was one of the organizers of Matisse’s school, which opened in 1908 to a group of about ten students.

Still Life: Flowers in a Vase, c. late 1911, by Patrick Henry Bruce

In the African Art gallery, I found masks and fertility gods.

In the Asian Art gallery, I found Mortuary Retinue, which reminded me of the Terra Cotta Warriors. Thirty-nine ceramic figures and animals form this retinue, which accompanied a deceased individual to his tomb. Varying heights, rudimentary facial features, hair styles, hats, and clothes distinguish the figures of Chinese soldiers from those of foreigners, who have mustaches, or minorities with long hair. The presence of foreign traders, Chinese court ladies and courtiers, and a dwarf further suggest the variety of inhabitants in the capital.

Mortuary Retinue, late 6th – early 7th century, Sui (581-618) or Tang (618-907) dynasty

Finally, I saw the Sweaters of Peace. For over a decade, Ellen Lesperance (forn 1971) has collected imagery of life at Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp (1981-2000), the separatist feminist camp that formed in protest of U.S. nuclear weapons storage in Berkshire, England.

Campers made and wore sweaters not only to keep their bodies warm but also to express their politics through knit-in symbols: rainbows, peace signs, battle axes, celestial skies. In these garments, Lesperance found a way to rethink figurative painting. Using Symbolcraft — a shorthand used by knitters in the U.S. that details the stitches needed to make a garment — each painting doubles as knitting instructions to reimagine the garment in a source image.

Baltimore Museum of Art

The Gatehouse provided a stunning first impression for those visiting William Wyman’s estate in the late 19th century. Wyman owned much of the land that is now Homewood campus. He loved nature and kept the grounds mostly undeveloped. The two major buildings he established here were the Villa, where he resided, and the Gatehouse, also known as Homewood Lodge, which was the public entrance to the estate.

Wyman had the Gatehouse made of a green stone called serpentine. This made it blend with the green forests surrounding it.

After Wyman gave the land to Johns Hopkins University in 1902, student groups met in this building. The Johns Hopkins News-Letter made the Gatehouse its home in October 1964, and remains there to this day.

Gatehouse – News Letter Office

I left the Baltimore Museum of Art and went to the Walters Art Museum.

Information about the exhibits and artwork are taken from signs at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

*Friday, February 21, 2020*

![fullsizeoutput_1c6ab Luzanna [Lousuanna Lujan] and Her Sisters, 1920, by Walter Ufer](https://wanderessencecom.files.wordpress.com/2020/11/fullsizeoutput_1c6ab.jpeg?w=410&resize=410%2C308&h=308#038;h=308)

Thank God for women like the Cone sisters and others of their generation who spent their massive wealth responsibly, dedicated to preserving and collecting as much art and culture as they could, back in the day, so that millions of people can share in its splendour and wonder and enjoy their collections long after they are gone. Unlike many of today’s trust fund babies who are only interested in collecting images of themselves doing stupid, selfish, pointless things that leave nothing behind but reflections of how much time they wasted and how much wealth and opportunity they squandered.

Beautiful exhibit and by the way, as such things go, this is a pretty terrific Impressionist gallery!

LikeLike

Yes, it is great when people who have money collect art and share it with the world. It seems most people with wealth hoard it and don’t do anything useful for society. I’d like to see more people donate huge amounts to worthy causes like Dolly Parton donating toward developing a Covid vaccine. Or to reversing climate change like Tom Steyer. Or to correcting income inequality. So many pressing issues that people who amass great sums of money could donate to.

LikeLike

Beautiful display of the collections. We usually just pass through Baltimore on our adventures unless its lunch time then we stop to eat crabs. Have a good day

LikeLike

Stopping to eat crabs in Baltimore is always a good option! We live just over an hour away, and this was my first time actually exploring parts of the city. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very impressive museum – both in variety and quality. I love to see collections that basically reflect someone’s hobby and yet blow you away with their value! Like Frick in NY, or our own Glasgow equivalent, Burrell. The wealth they had is unimaginable. I never camped at Greenham, but I did visit on one of the mass protest days.

LikeLike

It was an excellent museum, Anabel. Yes, the Cone sisters really had such a huge collection and it was simply their hobby. It must be nice to be wealthy enough to have such a hobby. I hope to make it to Glasgow one of these days, if we can ever travel abroad again. Now that we will have some leadership (after Jan 20), we can hopefully get things under control here. Interesting that you were involved with the Greenham protests. You do seem to be involved in a lot of causes! 🙂

LikeLike

I hope I’m not tempting fate by saying things can only get better!

LikeLike

It’s tough to live through these next 60 days until Biden is sworn in. I’m afraid of all kinds of nefarious undermining of our election, which is certainly being attempted at every turn!

LikeLike

What I’m reading is very scary.

LikeLike

It’s very scary living here in the midst of it all!

LikeLiked by 1 person